Exploration is one of the three pillars of tabletop role-playing games (TTRPGs). Yet, it is often the least supported. Rewarding exploration is the key to making the gaming group excited about it. Groups that explore more build a more characterful world. It’s an opportunity many groups miss.

It's The Destination, Not The Journey

There is a natural tension with exploration in many tabletop RPGs. Even in hex crawls, the party is usually moving towards a settlement, a landmark, or chasing a rumour. It’s very rare for a group to say “We ride north!” for no reason. The focus is on the destination.

Exploration, then, becomes an inconvenience. It’s a speed bump for the party to get over, delaying the actual fun. Additionally, it can feel like an obvious resource tax—a deliberate drain on inventory, party spells, and hit points—by the gamemaster (GM) so they don’t start an encounter loaded for bear.

Skip Rewarding Exploration & Go Right To The Action

Consequently, instead of having rewarding exploration, a common response is to skip it altogether. If the party starts the session right outside one of the dungeon’s entrances, they get right to the action. This is the easy option.

Combat and social encounters have obvious payoffs: loot, experience, information, story advancement. So, the temptation is to get to the dopamine hit without delay.

However, this misses a chance of meaningful player interaction with the world. Trevor Devall (of Me, Myself, and Die) points out if you cut travel from The Lord of the Rings trilogy, the 481,103 word epic that has defined much of modern fantasy becomes a relative haiku.

When there is nothing to gain, skipping to one of the dungeon entrances has its place. But there are other options, too.

The Montage

The other common response. This reduces travel down to a quick narration. Again, this an admission that party satisfaction is at the destination, and the gaming group wants to get to the good stuff ASAP—exploration not included.

Montages Plus Skill Checks

A variation on this is the inclusion of skill challenges. The GM introduces something like three difficulties faced by the party; players then describe how they tackled these problems, rolling skill checks as necessary. Rolls interpreted, the party arrives at their destination without much real-time delay.

The process doesn’t postpone the action for too long, with the added bonus of increasing player agency. Significantly, failure doesn’t threaten arrival at the destination, it functions purely as a resource tax.

Player-Created Montages

The One Ring RPG popularised a further variation to the montage approach. Instead of the GM creating the difficulties faced, the players do.

One player thinks up a problem the party encounters, and the next player narrates its solution. Then, they create a new problem, and the next player takes over; the process repeats until everyone has had a turn creating and solving a situation.

Dice rolls only have limited input and, in some systems, are optional or entirely removed from play. This will appeal to some groups a lot more than to others—some folk just want to roll fistfuls of dice.

It places a lot of agency with the players and exploration becomes meaningful. Its speed and comparatively light detail compared to combat and social encounters, though, suggests this style is still nervous about treating exploration as one of the three central pillars of play.

Similar to the travel skip, montages have their place at any tabletop group, but there are still more options out there.

Crunch Makes Rewarding Exploration?

At the other end of the spectrum there are systems that use a lot of crunch: rigid or complex rules to tackle exploration.

Often, crunch involves random encounter tables. Travelling at night often risks more dangerous results than during the day. Moving carefully or along well-travelled paths will reduce the risk further. However, these are just adding combat and social encounters to dilute the exploration sequence.

The appeal of random encounter tables lies in everyone—GM included—not knowing what will happen next. It definitely isn’t about the GM trying to avoid responsibility for the incoming pain. More seriously, random encounter tables also free up GM brain capacity for other things, or work as inspiration for those times when tiredness is creeping in or the caffeine is running out.

Resource Management Games

The crunch usually tracks food and water amounts, fuel, tiredness, and the like. Navigating becomes an actively rolled skill. The weather often has an impact on the party.

Again, some gaming groups will find this style of exploration more rewarding than others. Some groups find this builds tension, while others feel it damages immersion. It’s worth noting GMs tend to be a lot more enthusiastic about this kind of thing than players. Why? Where they see illusions of realism, players—at best—only get to keep what they already have.

In a lot of systems, resource tracking and hard skill challenges are a zero sum game. For many, here is the root of the problem with travel and exploration. In trying to make travel matter, a lot of systems don’t know how to handle it without treating it like a resource tax—and no one likes taxes without payoff.

So, how do groups make exploration rewarding and meaningful?

A Case Study Of Rewarding Exploration

In the video game Satisfactory, the player controls a pioneer stranded on a world unknown. Starting with nothing but chunks of iron and copper ore, they will eventually build up a massive infrastructure of conveyor belts, trains, drones, and dimensional portals that cover the land.

Part of Satisfactory’s brilliance lies in how rewarding exploration happens naturally. To upgrade, you need more resources found in areas further afield. The incentive is obvious: if you want to progress the game and get cooler tech, you need to get to those new areas.

Have A Range Of Rewards & Make Them Plentiful

However, this is one of the rewards on offer. Along the way, the player will encounter alien lifeforms, power slugs, and strange alien artifacts. Spaced around the map so liberally, it is impossible to go in any direction for long without finding something useful.

Many are easy to acquire. But the more the player has to work, the bigger the payoff. Significantly, these finds never stop being useful.

Harvested alien DNA is the most valuable trading item in the game. The player never stops building, so the demand for power slugs’ efficiency boosts never ends. Meanwhile, the alien artifacts offer lore, intrigue, and exotic tech.

None of these rewards make the game too easy. Furthermore, it’s certainly possible for a player to finish the game without bothering to hunt for any of them. However, they offer such tempting quality of life improvements, it’s nearly always worthwhile having a wander.

Rewarding Exploration Through Variety

Consider seeding the wilds of the gaming group’s world with a valuable resource—something expensive, but not a luxury. Roving traders that deal in secrets and lore that can only be reached while dreaming in the desert. Strange artifacts that the party can’t immediately use, but a friendly wizard or scientist would be very grateful to experiment on. Volcanic tree resin that briefly empowers weapons.

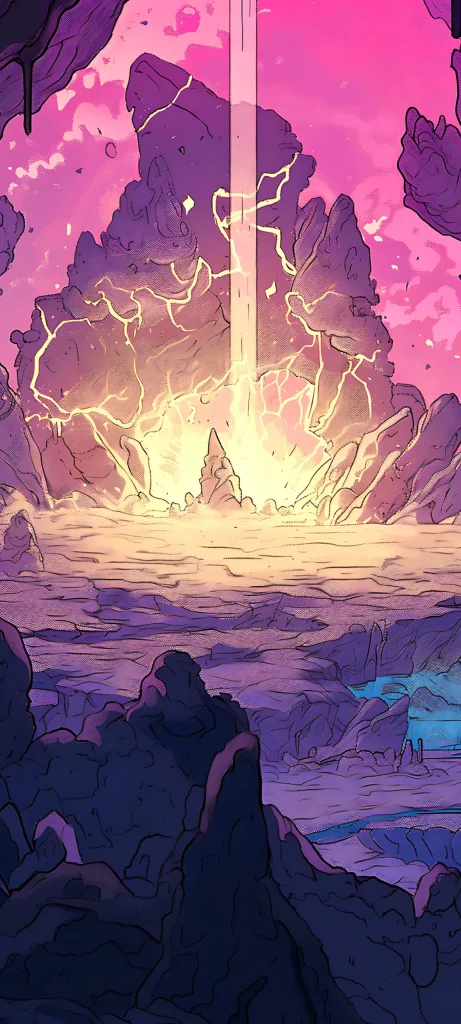

Variety in all things—the reward types, locations, gathering processes, dangers involved—are essential. Have fun with the locations, especially. If combat encounters need fun monsters, and social encounters need interesting NPCs, exploration demands cool or unusual places. Treat the mind and stimulate as many of the other senses as possible.

Combine Visuals With Audio

Music is incredibly useful here. Perhaps more than any other encounter type, players have a chance to absorb the atmosphere of the world they are co-creating. Without an immediate threat or pressing dialogue, there’s just that bit more of a chance to let the imagination engage.

Both Opus and playlists built right out of the Michael Ghelfi Studios database can work brilliantly. One thing to add, though, is don’t disregard unusual combinations. Walking through a forest during the day has an obvious ambiance choice (but if that doesn’t suit, there are 142 and counting more forest related tracks to choose from).

Mismatch Intentionally

However, players given the visual aid of a beautiful, peaceful forest picture while hearing rolling ocean waves and tinkling bells from Dreamwalking will believe things are not so simple. Likewise, if they have the same picture but are listening to Hall of Nightmares, they will believe something horrifying is likely to happen or has already occurred in this tranquil place.

Make the eyes and ears work together and against each other during the course of the gaming session. Obvious pairings let players focus on the words of the GM and the other players because everything makes sense—things can be taken at face value.

Unusual combinations will make players focus on the unspoken. Minds will try and make connections to bridge the information gap—what isn’t the GM saying? The human mind has the irresistible urge to solve puzzles. This will do a lot of the hard work for building atmosphere and can foreshadow a future reveal.

Avoid Lazy Descriptions

For rewarding exploration, have visuals that are always somewhere between interesting and spectacular. Above all, keep them varied. In Satisfactory, the pioneer will climb massive peaks and delve into deep, dank cave systems. Sweeping red deserts give over to luminous megaflora forests, ancient craters, and still turquoise lakes. All of these hold strange giant rock formations and hints of lost alien civilisations.

Verticality, colour palettes, spatial atmosphere, scale, difficulty in traversal, and danger levels are all variables the game’s developers shift.

But here’s the thing: Satisfactory is just a computer game. Computer hardware and its genre act as hard limits on what the player can experience. A TTRPG has fewer limits. Unleash the imagination: imagine giant glass pyramids hovering over fields of bone; crystal caves singing melodies that alter memory; pathways burned into the sky by shooting stars.

Rewarding Exploration Builds World Character

Another reason that systems find combat and social encounters easier to build around is they have an obvious focal point. The party has an NPC or creature they must find and engage with. Exploration has no obvious figure for the players to focus on.

Unless the world itself can feel like a character.

In Satisfactory, the player will encounter creatures of all dispositions—placid, territorial, and aggressive hunters. They will dash, waddle, skitter, gallop, and soar. Some will come up to the pioneer’s knee, others will be larger than a multi-storey building. The pioneer can harvest only a handful of them; some they can’t even touch.

At no point will the player ever know their real names. The pioneer is an engineer, not a scientist. They are focused on surviving and exploiting, not observing and cataloguing. Even the animals they can harvest are ambiguously referred to as hogs, stingers, spitters, and hatchers.

The wildlife are an extension of the world’s character: it’s weird and unknowable. The lore teasers communicated to the player are surreal and creepy enough they’d be at home on Citadel Station—not the Star Wars one, the scary one.

Have Little Opportunities Everywhere

For the TTRPG group, the land, the wildlife, architecture, the bones the current civilisation has been built on—all of these are windows into their world. How the locals treat their dead, their children, their foes—both defeated and current—as well as who their champions are give more hints.

Also remember people and cultures are rarely homogenous. They are usually messy, a mix of victories, passions, and tragedies. The different perspectives will show as much about a people’s similarities—past and present—as they do their differences.

The granddaddy of fantasy worldbuilding, Tolkien, had five different Elven groups and seven dwarf clans alone.

Build While Playing

It isn’t necessary to have all this worked out before a game; these provide chances for the group to develop the world’s character during a session naturally. However, if players are going to enjoy interacting with the world, and wish to do it with any regularity, they must get worthwhile rewards for their efforts.

The best way to find these chances is to travel and explore. The type and range of rewards on offer will depend on the group and the game they’re running; however, for rewarding exploration, variety and availability should be high.

An Important Reminder

It’s worth stating, all of the methods of dealing with travel—the skip, montage, resource tracking, and others—are useful tools for any gaming group and all can find their way into the same game, even the same session.

Narrative pacing, tension, and table energy levels are all factors that might dictate one method is better than the others in the moment. However, don’t miss the chance for the table to make exploration more rewarding, the world more characterful.

Rewarding Exploration For A Great Game

The key to making exploration and travel more fun is in the rewards. Nothing should be game-breaking or quest-defining. However, a variety of rewards, readily available, will make players want to get out and explore the world a lot more than any resource tax system alone.

By travelling more, the group naturally has more chances to characterize their world. As these small opportunities build up, the world becomes that bit cooler, more special, unique. Give it a try.

Good luck!