Stress is one of the biggest influences on who people are. From socializing with other gamers, to empathising with characters in dangerous situations, tabletop roleplaying games (TTRPGs) can increase people’s stress levels in many ways. Handling stress, then, is an essential part of any happy—and healthy—gaming group.

Understanding Stress

In the 1930s, Hans Selye presented his theory on stress. This is still a major part of people’s understanding of the topic today. Many people know about the “stress hormone” cortisol and its effects on the body. A fight or flight response, people usually see sources of stress as negative. In other words, they focus on distress.

Fewer people are familiar with Selye’s idea of eustress. This makes cortisol too, but it comes from positive events. Real world examples might include a wedding proposal, getting a promotion, or winning a competition. For gamers, this means the body can feel as much stress defeating a Big Bad as losing a party member.

The other thing many people forget is stress–positive or negative–is good for everyone. Among other things, it helps people work harder, and it boosts their powers of memory. There is no escaping stress, and in small amounts, that’s fine. However, too much stress, over a long period of time, is where the problems begin.

This isn’t a dedicated mental health article, and there is lots of advice online on how to deal with too much stress. However, a player probably won’t go for a brisk walk mid-game when tensions are high.

Handling Stress At The Table

If the game makes players feel far too uncomfortable, they might use tools like an X card. Other groups prefer using something similar to Mike Shea’s “Let’s pause for a minute.” This is an interruption anyone can use at any time to voice concerns (as well as making sure everyone understands a situation, possible player tactics, etc.)

Ultimately, communication is a group’s best weapon for making everyone happy, so use whichever tool suits the table.

Table Chat & Play Expectations

![dog-838281_640 A close up photo of a dog staring at the camera. Illustrates [alt text].](https://www.michaelghelfistudios.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/dog-838281_640.webp)

Less obvious ways for handling stress include letting the group's banter flow and mixing up the game.

A common complaint from gamemasters (GMs) is that players are joking too much at the table. There are definitely times when interrupting the GM is bad play—remember communication is the best cure-all for this, but everyone should remember it’s a game and having fun is the goal.

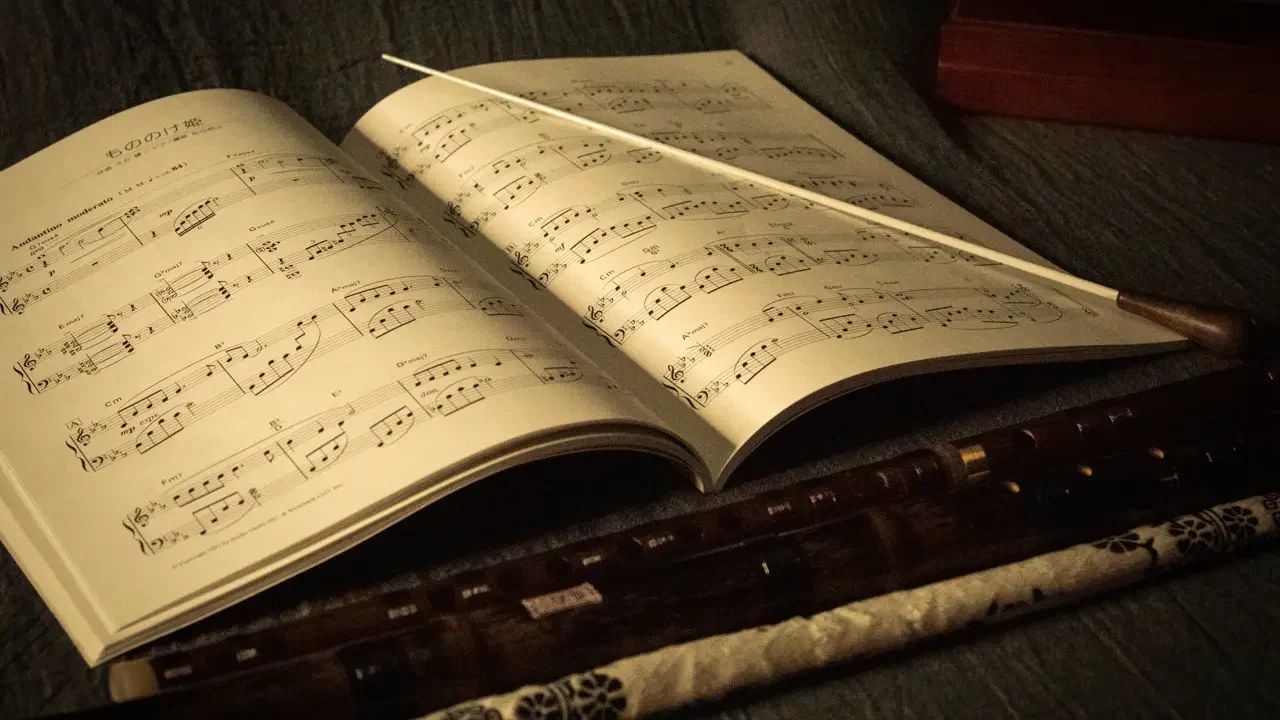

On a related note, Sean McCoy, co-creator of the major hit Mothership, highlights the player characters (PCs) are the ones experiencing the horror. In the GM’s guide—the Warden’s Operations Manual—he says the goal is to target the PCs, never the players. No matter how good a GM is, players will rarely forget they are playing make believe and throwing dice to determine outcomes; on the occasions they do, it’s never for long.

Sean also reminds GMs that players have probably had a lot of exposure to media; they have already watched and listened to a lot. Consequently, it'll be very hard to get a response above “Wow, that’s gross!” during a game—getting a stronger response is unrealistic and it should never be a goal. Trying will only create unnecessary stress for the GM, and probably the players, too.

Sean is focusing on horror, but this applies equally to in-game moments of tragedy, love, awe, rage, etc. Expecting everyone at the table to have full immersion, to truly become their characters for the whole session, is an impossible dream. Therefore, so long as the jokes are well timed, let the banter flow. The goal of the game is fun, and laughter is some of the best medicine for stress.

Change The Game

Another approach to handling stress for the group is to play a one-shot, or short arc finished within a few sessions.

Playing different characters, or a different system altogether, will help break people out of any negative mindset. The group can always return to the main game when they are ready, but can do so feeling refreshed and recharged.

Handling Stress In-Game

First, both GMs and drama llama players—not that kind, this kind—should take care of themselves; high levels of tension maintained for a long period of time are neither particularly fun nor healthy.

Consequently, it’s essential to play low-stakes events after intense situations once in a while. Remembering distress and eustress both need resolving, GMs should have these mini-scenarios ready after any big event—good or bad.

Make it clear—telling the players directly if needed—nothing terrible can happen if the event goes wrong. Failure might not even be an option. Interpreting bad dice rolls could mean the party only loses time or receives less rewards than if they’d rolled well.

Some ideas for releasing eustress include a feast, a festival, or a hunt for an under-powered villain. One thing of note is to be careful during long ceremony sequences. Players are nearly entirely passive during these; they want to be making choices and probably rolling dice, so make those happen instead.

Ideas for relieving distress include hunting an under-powered villain again, as well as funerals and wakes. The latter have the added bonus of being great worldbuilding opportunities, showing how the locals treat their dead. Don't be afraid to make it weird!

Variety Helps Handling Stress

Besides relieving stress, these mini-scenarios can also work to vary the tone and challenges the party encounter. These situations should require a combination of strength and intelligence. In other words, give the players the chance to use abilities, spells, and tactics they wouldn't normally because optimisation is less important.

Examples of neutral low stakes missions or quests could see the party pathfinding a new trade route, harvesting a rare resource from migrating animals, or solving a non-too-serious case of theft.

These events don’t have to be connected to the ongoing narrative, but their rewards should be meaningful. They should bring benefits to the PCs, or to the local area that the party will benefit from later.

Find Opportunities Everywhere

Sometimes, finding a break in the action is less obvious. If the party are in a really dangerous area, it may seem unnatural for them to have the chance to relax. However, even in enemy territory, there will be places without hostile patrols. This applies to all the previous examples as well, but especially here, non-player characters (NPCs) are a wonderful tool.

NPC travellers, refugees, and strange merchants can be found anywhere. Even bandits and enemy soldiers get tired or simply don’t want to risk their lives. Go ham on their mannerisms, their voice, what they want, and what they’re willing to give. The players will likely realise this NPC isn’t immediately dangerous and they can relax, if only for a while—and, if they don’t realise, tell them.

Keep Lulls Meaningful & Interactive

![pexels-fauxels-3184431 A photo of several people joining their hands together at the center, as a teamwork effort. Illustrates [alt text].](https://www.michaelghelfistudios.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/pexels-fauxels-3184431.webp)

Handling stress in-game for some groups means pure role-playing improv. Others will much prefer the dice never stop rolling. For these groups in particular, look for any chance to involve meaningful dice rolls.

For instance, a funeral event for a dead PC could see the players performing tasks that ensure the character’s soul safe travel to the next plane; or, it could make resurrection possible later–bad rolls meaning a delay, not outright failure, if this is a stress-releasing event.

Check different GM’s guides for more ideas. Many systems like Dungeons & Dragons, Shadowdark, and Knave all have differing rules and roll tables to take inspiration from. Use their rules for downtime and carousing as written, or adjust to match the group’s needs.

Consider Unnecessary Sources Of Stress

One other place that stress can arise from are the rules of the game. Most, if not all, gameplay mechanics should have a payoff for the players.

Despite its horror theme and use of panic mechanics, Free League’s Alien RP gives PCs a bonus for low levels of stress—much like in real life. Stress gives the players more dice to roll, resulting in higher the chance of success. Even if those extra dice trigger a panic test, results from the game's "Panic Table" are very gentle. In this regard, the really dangerous results are only possible once the player is throwing fistfuls of dice deeper into a session. So initially, stress is good; it’s a risk, but it gives the PC a very real reward.

Compare this, then, with travel rules that give nothing to the player for having enough food. However, the same rules create lots of disadvantages if the player starts failing rolls. Mechanics that challenge the party, but offer a real reward—with or without risk attached—are great design. A lot of homebrew rules forget this as creators focus too much on attempts at realism.

Mechanics that both constrain players and make them do careful bookkeeping for no return can be sources of stress at the table.

Communication Never Stops

Again, communication is a group’s best weapon. There are groups out there that will like this level of bookkeeping; it’s equally important to say what everyone is enjoying at the table as much as what they don’t.

In his video on Session Zeroes, Seth Skorkowsky points out that the dialogue amongst the group should never stop. Whether it’s session zero, or session who knows after 43 years, players and GMs should have honest and open communication between each other.

Openly talk about the stuff people have loved doing, and the things that didn’t work as well. This is the fastest and most effective way to identify and resolve sources of stress at the table. A group that can communicate freely is likely a happy and healthy group.

Handling Stress Keeps A Gaming Group Happy

![pexels-biasousa-2213050 A photo of a woman holding a lightbulb. Illustrates [alt text].](https://www.michaelghelfistudios.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/pexels-biasousa-2213050.webp)

Stress is something everyone feels, and in low amounts it is perfectly healthy. However, remembering rules, improvising, and empathising with characters are just some of the sources of stress at the table.

It’s important to be mindful of both positive and negative sources of stress. Create encounters or even whole sessions designed to release this stress in the group. And above all, make sure everyone is freely communicating honestly and openly. Give both the narrative and the people at the table a chance to breathe.

Good luck!