Designing villains that are interesting and challenging is an important skill for any gamemaster (GM). Heroes are only as epic as the challenges they overcome, and villains are often their ultimate test. The following guide will give ideas on how to make your gaming group’s next villain a really memorable one.

Creating Villains' Themes

Often the first step is to decide their themes and motivations. Although many GMs will design these together, to keep things simple, this guide will look at them one at a time.

The themes of a villain are the ideas they represent. For instance, the Batman’s Joker is a symbol of unending chaos; Star Wars’ Darth Vader represents oppression and control through fear; The Lord of the Rings’ Sauron is the idea of might makes right.

These themes may copy a campaign’s themes—if there are any—but they don’t have to.

In the case of Sauron, one of Tolkien’s central themes is evil can never truly create, only corrupt. The Kings of Men turning into the Nazgûl is a prime example of this.

However, Sauron’s desire to control everything through violence—the central threat powering the trilogy—comes from his belief in might makes right; as the strongest being on Middle Earth, at least in his eye, it is only natural he should rule everything.

As with much of this process, a helpful source of inspiration is the group’s player characters (PCs). White room designing—creating villains with no reference to the party—can work, but villains that oppose the PCs’ themes are more memorable.

Sauron wants solo control through force because the Fellowship represents the strength of friendship and freedom of life. Similarly, the Batman’s Joker is only a symbol of unending chaos because the Batman wants order and resolution.

Themes As Dark Mirrors

In Star Wars, Luke wants peace through freedom and hope, so Vader wants peace through total control and fear. Villains aiming for the same end result as the PCs can show the dangers of going too far with an idea, or the problems of using particular methods.

Here are some starter ideas for themes: corruption of an ideal (e.g. peace or happiness), the dangers of obsession, evil hidden in plain sight, the cost of immortality, anti-nature/oppression of industry, and everything ends.

Designing Villains' Motivations

![find-out-why A photo of a lady staring at the mirror in a contemplative manner. Illustrates [alt text].](https://www.michaelghelfistudios.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/find-out-why.webp)

Some GMs find themes too abstract, so many start here. When creating a villain’s motivations, the key questions are what do they want and why. A villain wanting money or power isn’t enough—what do they want to do with it?

Designing villains trying to reshape the world are a quick-start choice. It places people and things the PCs may care about in danger straight away.

Sauron’s plans put all of Middle Earth at risk. Similarly, SHODAN, the super-AI from the System Shock series, sees her rise to godhood as natural; however, there will be no room for people as she reshapes the galaxy in her image.

Survival is another quick-start motivator.

When in danger, characters can become villains as they do anything to survive. For example, Saruman, another antagonist in Tolkien’s trilogy, believes he can outsmart Sauron. However, he also thinks there is no real way to defeat him; the choice is to join with the Dark Lord or die.

![woman-peeking-through-door-10802159 A photo of a suspicious woman sneakily entering a room. Illustrates [alt text].](https://www.michaelghelfistudios.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/woman-peeking-through-door-10802159.webp)

Wanting to be important drives many villains.

Dracula wishes to move to London mostly out of pride and ambition. He wants to swap quiet, out-of-the-way Transylvania for the centre of the British Empire—the largest colonial power of the time. He wants to corrupt and influence that power; he wants to matter again.

Designing Complicated Villains

![DogUnicorn.pexels-mark-glancy-721708-1564506 A photo of a dog in a unicorn costume. Illustrates [alt text].](https://www.michaelghelfistudios.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/DogUnicorn.pexels-mark-glancy-721708-1564506.webp)

More complicated villains often twist well-meaning motivations. Francis Ford Coppola’s Godfather Part One and Two has mafia bosses who will do anything to protect their family (the Godfather duology. Ignore anything else. It is a lie).

Frankenstein’s monster only wanted friends and a companion. It’s the denial and terrible treatment he gets from people that turns him into an antagonist.

![pexels-tanya-gorelova-2199357-3860311 A photo of a cute puppy. Illustrates [alt text].](https://www.michaelghelfistudios.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/pexels-tanya-gorelova-2199357-3860311.webp)

If GM’s want more depth, ask a third question—what does the villain fear? Trying to stop something happening can be as powerful as trying to get something. As an aside, thinking up fears, self-interests, and points of pride are a great way to improvise any character!

Starter ideas for motivations: fix society, revenge, protect someone, eternal fame, save people from themselves, save the world from people, fear of death, getting what they deserve, and nothing matters.

Deciding The Villains' Power Level

Next, decide how powerful the villain is. This can also suggest how far along they are with their plans. Here are four levels to choose from:

Designing Villains Below The PCs’ Level

![dog-7205842_640 A photo of a brown dog with a pacifier in its mouth. Illustrates [alt text].](https://www.michaelghelfistudios.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/dog-7205842_640.webp)

Under-powered villains are simple threats. They may be too early on in their plans to be a big danger. If they survive their meeting with the party—a big if—they can become recurring villains who get stronger as time goes on.

Additionally, under-powered villains boost players’ power fantasy—remember challenges shouldn’t always be equal to the party. Plus, they can also work as sub-bosses for a bigger threat, becoming useful sources of foreshadowing.

![pexels-pavel-danilyuk-7221566 A photo of a woman holding golden playing cards, hiding behind them in a mysterious manner. Illustrates [alt text].](https://www.michaelghelfistudios.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/pexels-pavel-danilyuk-7221566.webp)

Lower level villains are a great break from the main campaign; they offer variety without needing too much energy; additionally, there is a very low risk of derailing the focus of the main narrative.

Examples include: bandit leaders, apprentice scientists/mages, criminal or military captains, or local pests—e.g. a roving wolf pack, a hungry roc, a monstrous spider brood mother.

Villains Of Similar Level

![pexels-ck-lacandazo-1269584-3445161 A photo of a woman holding a snake. Illustrates [alt text].](https://www.michaelghelfistudios.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/pexels-ck-lacandazo-1269584-3445161.webp)

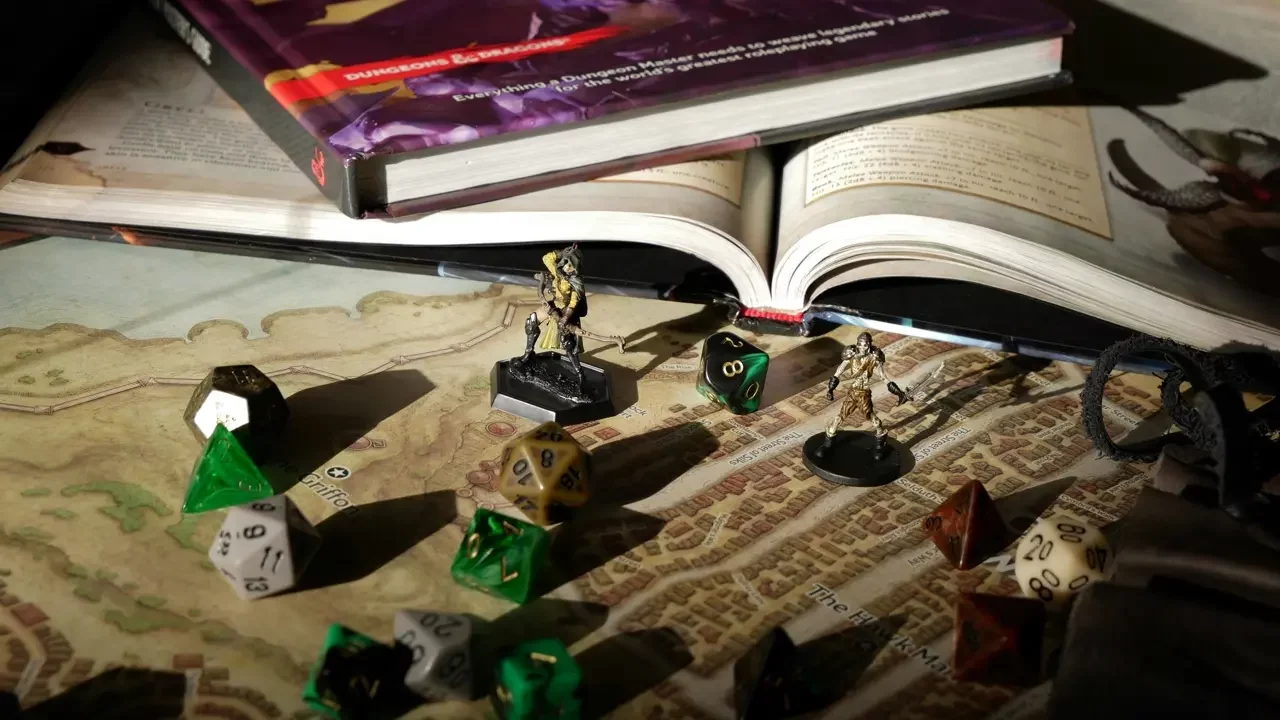

These are a challenge for the party, but victory is likely. Written adventures often use a series of these, each villain encountered a match for the increasingly powerful PCs—great for some groups, but others will dislike the campaign treadmill effect.

It’s difficult to give examples here, as it depends on the power level of the group’s party. However, there are plenty of online resources to help. For instance, Kobold Fight Club and Sly Flourish’s Lazy Encounter Benchmark are both very popular Dungeons and Dragons (D&D) 5e calculators.

Villains Above The Party’s Level

![DogSuperdog.unsplash.k-e-7-ToFEHzMNw A photo of a Boxer dog in a Superman costume. Illustrates [alt text].](https://www.michaelghelfistudios.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/DogSuperdog.unsplash.k-e-7-ToFEHzMNw.webp)

These will challenge the party and defeat is a very real possibility. These villains may be very far along with their plans. They are also very likely to have strong infrastructure supporting their power base.

Again, it is difficult to give examples here, but foreshadowing their power is essential. The PCs should know long before any fight the danger level. Indeed, combat might not be the best way to defeat them.

![SFHaduken.pexels-joagbriel-1765126 An artistic photo showing a guy "magically pushing" another into the air. Illustrates [alt text].](https://www.michaelghelfistudios.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/SFHaduken.pexels-joagbriel-1765126.webp)

Weakening the villain could be an initial goal for the party. Quests or missions that find out their primary objective, damage their infrastructure, or stop them from getting more power all work well.

If the PCs do start a fight, try to ensure they have a way to retreat if the battle goes badly. Allies may be useful, but be careful to avoid stealing the glory from the party.

Villains Way Above The PCs’ Level

These usually work as the Big Bads of a campaign. Their power level is so high—especially at the beginning of the story—they probably do not see the party as a threat.

This is very useful, because it means they can encounter the party without risking a fight. The party can get to know them directly—their perspective, motivations, strengths, weaknesses—and build an understanding of them.

In Curse of Strahd, the Vampire Lord is on every random encounter table in the adventure, but he isn’t likely to be hostile most of the time. On top of the set-piece encounters, the party should have encountered Strahd many times before the final battle.

Curse of Strahd is consistently voted most popular adventure book for 5e partly because the players spend so much time getting to know him. They learn his hopes, his mistakes, his debts, and his terrible brutality.

He is obviously evil, so the party can feel no hesitation in fighting him. However, they will learn the tragedies that led him to his current life.

Don't Hide Tier 4 Villains

Introduce Big Bads early with rumours if a face-to-face isn’t possible. It doesn’t make sense for a creature with near god-like power to be a surprise to anyone at the end of a campaign. Movies can sometimes do this, good TTRPGs cannot.

Other D&D adventure books do less well because there is confusion over who the primary villain is. Others reveal the villain in the final act as a weak twist with no foreshadowing; consequently, the party have no chance to build a deep connection with them.

![dog-5584135_640 A photo of a black dog in the beach. Illustrates [alt text].](https://www.michaelghelfistudios.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/dog-5584135_640.webp)

One thing to note, many GMs make the mistake of thinking a Big Bad is necessary for every campaign. This can be a problem because it means the stakes will be high as well. If this continues campaign after campaign, it can lead to burn out.

It takes a lot of energy to play lengthy campaigns. Unless the characters are starting at very high levels, or it’s a cosmic horror game, it will take a long time before the PCs face the Big Bad. Some groups will run out of energy before they reach the final act.

How The Villains Influence The World

The next step is to consider how the villain influences the world. Choose or combine muscle, science/magic, or social approaches.

Muscle Villains

![HEADERKnightEyeslit.unsplash.carlos-felipe-ramirez-mesa-X9nrbX_Scn4 A close up photograph of a gold-lined medieval helm. Illustrates [alt text].](https://www.michaelghelfistudios.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/HEADERKnightEyeslit.unsplash.carlos-felipe-ramirez-mesa-X9nrbX_Scn4.webp)

Muscle villains are army generals, assassins, and champion fighters. They will seek to conquer or wipe out enemies and rivals through intimidation and force of arms.

Muscle villains will look to capture places with tactical advantages, gather soldiers, and break their enemy’s supply lines. Getting better weapons is high on their to-do list. They are direct, and will try to solve problems with a sledgehammer.

Science/Magic Villains

![halloween-6715733_1280 A photo of a man in a mystical fantasy cosplay controlling a magical orb. Illustrates [alt text].](https://www.michaelghelfistudios.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/halloween-6715733_1280.webp)

Science or magic villains are archmages and technology pioneers. They use tech and powers no one else does. Likely weak in a straight fight, they will use their gadgets and spells to smash or strangle opposition.

Science/magic villains will look for rare resources, artifacts, and rituals that will increase their power. They will also want to protect their own supply lines and laboratory while stealing or destroying rivals’ work. Testing their latest discovery will also be a high priority.

Social Villains

Social villains are politicians and people who use their rank or charisma to manipulate people. They will rarely fight an opponent directly, and may even hide their attacks, placing the blame on others.

Social villains deal in information. Knowledge—getting it, holding it, hiding it—is power for them. More power means access to even more information. They will also work extremely hard to protect their reputation—both their real one and any fake ones.

Social villains will often be busy silencing witnesses, blackmailing, protecting powerful people useful to them, and starting wars between rivals to keep them weak.

Beasts And Aliens

Some villains won't think like people. However, they will still have motivations.

Simple creatures will want to find food and a mate. On top of that, some will aggressively protect their territory, want to expand it, or be in the process of setting up a new home.

Creatures that have a hibernation cycle or are emigrating will want to fatten up before they begin. Some may be running away from a larger predator.

Alien enemies could have any motivation under the stars, though the need to survive, grow, and reproduce are likely. If their motivations are impossible to understand, then it is often better to focus on their cults and human agents for a campaign.

Designing Villains With A Sense Of Honour

![NoEntry.pixabay.panel-2091780_1280 A street sign showing a hand grabbing a rectangle. Illustrates [alt text].](https://www.michaelghelfistudios.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/NoEntry.pixabay.panel-2091780_1280.webp)

In No Country for Old Men—both the book and film, the assassin Anton Chigurgh sees himself as a simple policeman of fate. He lets a coin toss decide whether someone will die. If the coin tells him to, he will leave them alive.

Villains with the same response for every situation will struggle to be memorable. Villains become far more interesting from what they won’t do. What is the personal code they won’t break? What actions do they see as wrong?

Designing Villains' Weaknesses

![pexels-freestocks-688961 A photo of a French Bulldog eagerly eyeing a bowl of snacks. Illustrates [alt text].](https://www.michaelghelfistudios.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/pexels-freestocks-688961.webp)

Another common mistake GMs make is for their villain to know everything or seem too well-prepared. In his series The Dungeon Master Experience, Chris Perkins points out great villains make mistakes or miscalculate.

In his example, an evil silver dragon landed on a balcony to taunt the PCs. Chris made a roll and decided the balcony collapsed under the weight of this magnificent beast, sending it crashing to the ground below. His players loved it.

![pexels-shvetsa-4588016 A photo of a shiba inu dog wearing a pink shower cap. Illustrates [alt text].](https://www.michaelghelfistudios.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/pexels-shvetsa-4588016.webp)

Give villains blind spots. Things they believe can never happen, or their pride not seeing the danger. Have cut-scenes where they find what the party have done to their infrastructure; show their frustration; show their surprise.

Give Villains Signatures

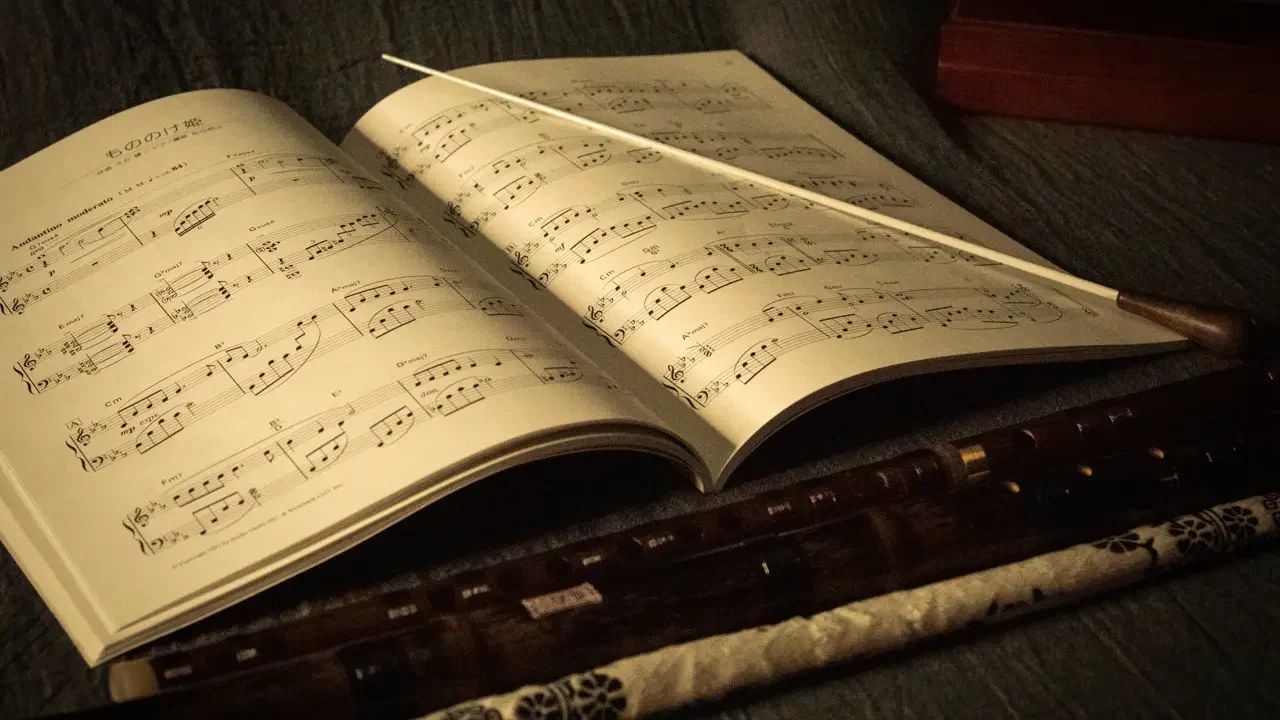

Audio can work brilliantly here. Once players connect a track with the villain, GMs can use it to foreshadow their entrance. Obvious themes like this can work, or for a more subtle approach, use something like this .

Have them act and speak consistently different to everyone else around them. Perhaps they have a way of playing with daggers, a catchphrase, or always wait more than two seconds before responding.

Designing Villains' Development

Lastly, it is a brave GM that believes any villain will see more than one encounter with the party. Unless they are far above the PC’s power level, it’s very likely the players will try and end the villain permanently, at the earliest opportunity.

So, planning recurring villains is a real problem. The best advice is to let it happen naturally.

Opportunities come when the party leave them alive, or they can function quietly in the background—with the party’s knowledge, but just out reach. Avoid GM intervention with escapes out of nowhere—it just doesn’t feel good for anyone.

Design Memorable Villains

Designing villains who are memorable for the table does take a bit of thought. Using this guide as inspiration, start with their theme and motivations, and go from there. With practice, making brilliant villains will be quick and fun!

Good luck!